The island of Jamaica remained under Spanish rule for nearly two centuries, from the first time Christopher Columbus set foot on its shores in 1494 until 1655 when the British arrived. During their rule, the Spanish enslaved the native Taino Indians, also known as the Arawaks, who quickly succumbed to the conditions of slavery and from diseases introduced by the Spanish conquerers. The majority died leaving the Spanish with limited options for supplementing their dwindling workforce, so they turned to the importation of African slaves, a practice that was replicated throughout the Spanish territories in the Caribbean and the Americas.

By 1530, slave revolts had broken out in Mexico, Hispaniola and Panama with many fleeing to create independent colonies. The Spanish called these free slaves "Maroons," a word derived from "Cimarron," which means "fierce" or "unruly". Ironically the name is also an apt description of a people marooned on lands far from home with no way to return home.

The British conquest of Jamaica in 1655, forced the Spanish to flee to the northern coast of Jamaica, and from there most Spanish colonists fled from the island, but some remained to form a resistance force to fight the British under the leadership of Don Christobal de Yassi. Many Spanish slaves took the opportunity to join the Maroons who had previously ran away from the Spanish masters and set up home bases in the interior mountains. Of the slaves that chose not to leave with the Spanish, some escaped to join the Maroons of their own volition, while others were encouraged to do so by the Spanish rearguard in order to help them hinder the progress of the British. Promises for future manumission made the suggestion palatable; the possibility of freedom making the endeavor worthy of the risk.

For the Maroons the idea of trading one master for another along with promises of manumission were sufficient incentive to impede the British efforts to drive the Spaniards from Jamaica. This led to the Spanish occupiers wrongly concluding that the Maroons were loyal to the Spanish crown. This notion eventually proved wrong when the first British governor of the island, Edward D'Oyley previously a lieutenant-colonel in General Robert Venables's regiment, built an alliance with a Maroon leader who was instrumental in routing the remaining Spaniards from the island. By 1660, the last of the Spanish had fled for Cuba.

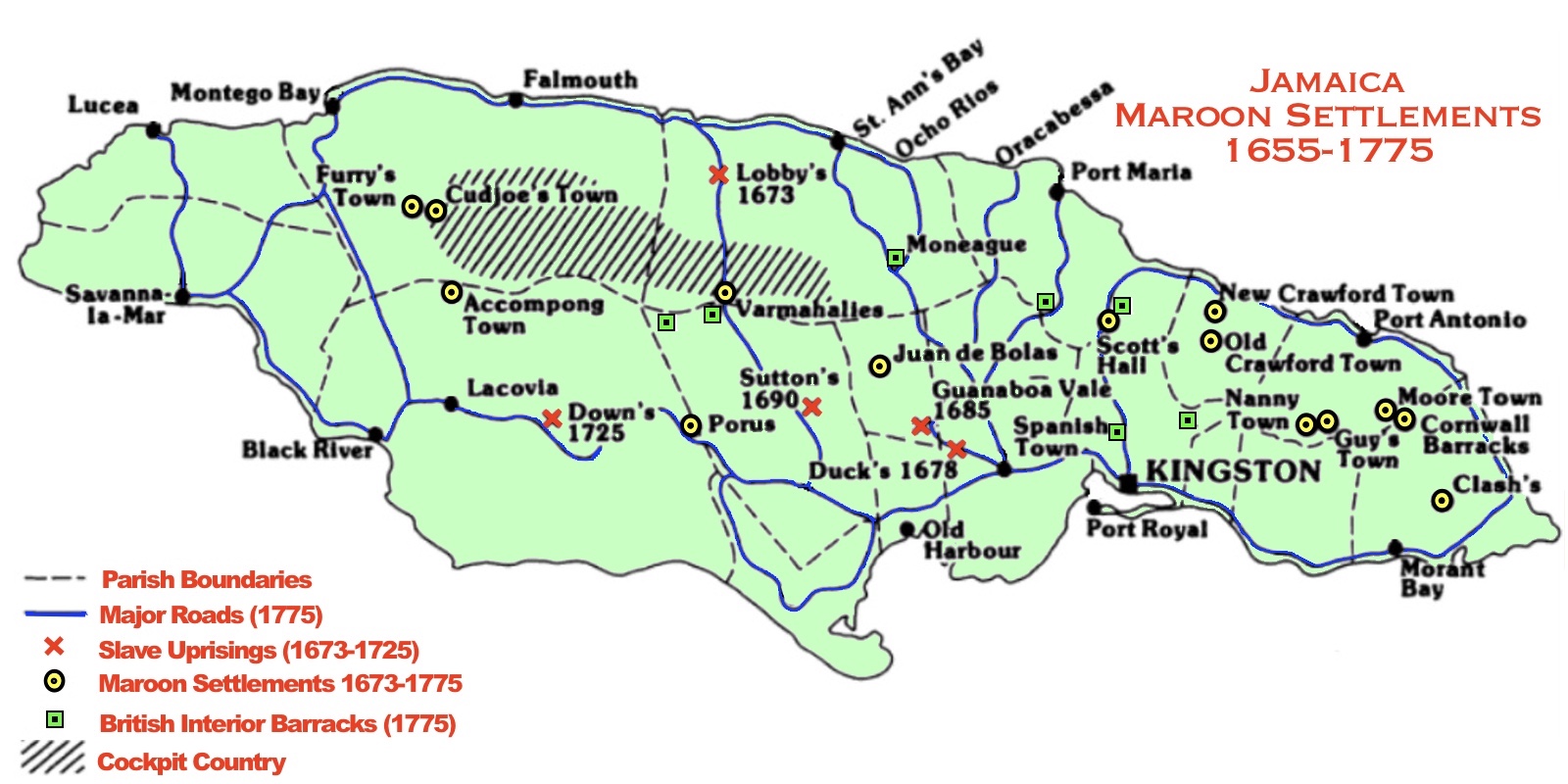

There were initially four main polinks, or mountain farms, established by the maroons during the first ten years of English occupation. The main one was located in Lluidas Vale -- currently also known as Worthy Park -- under the leadership of a maroon leader named Juan Lubolo, later known to the English as Juan de Bolas. There were two to the west; Vermahalies under the command of a Maroon leader called Juan De Serras and another in Porus. A fourth existed to the east in the Blue Mountains where those maroons existed in relative seclusion and isolation and is believed to have coexisted and possibly cohabitated with the few remaining Taino Indians who had fled Spanish rule to the relative safety of the Blue Mountains.

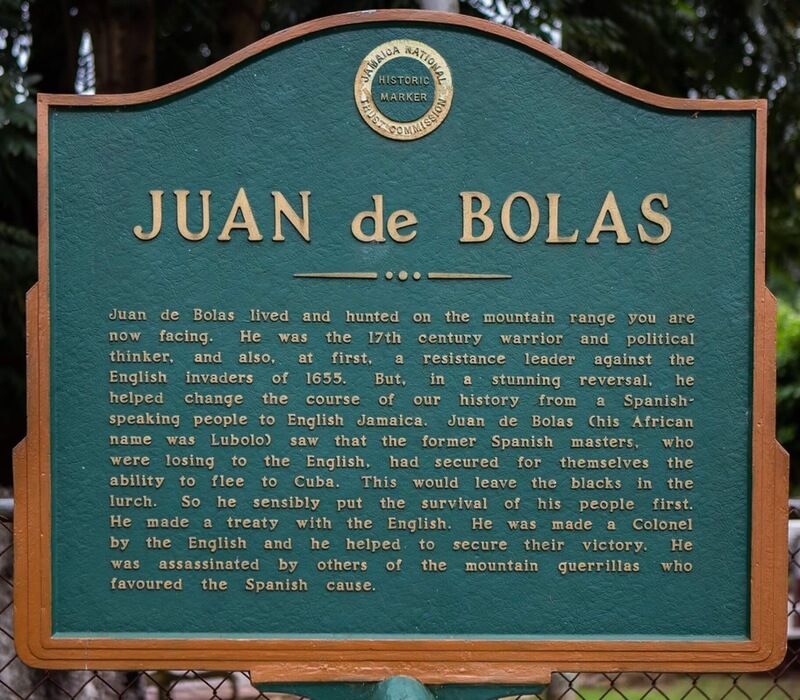

With dreams of freedom evoked by Spanish promises of manumission, the early alliance between the Maroons and the Spanish were initially effective in thwarting the British, but as the promised arrival of large scale spanish reinforcements failed to materialize, so did the hope of ever gaining freedom, and so, Juan de Bolas decided an actual settlement with the British, who far outnumbered the remaining Spanish, was a much better bet compared to the options proffered by the Spanish.

Memorial in Lluidas Vale. Photo courtesy of Diana Thorborn

Juan de Bolas lived and hunted on the mountain range you are facing. He was the 17th century warrior and political thinker, and also, at first, a resistance leader against the English invaders of 1655. But, in a stunning reversal, he helped change the course of our history from a Spanish-speaking people to English Jamaica. Juan de Bolas (his African name was Lubolo) saw that the former Spanish masters, who were losing to the English, had secured for themselves the ability to flee to Cuba. This would leave the blacks in the lurch. So he sensibly put the survival of his people first. He made a treaty with the English. He was made a Colonel by the English and he helped to secure their victory. He was assassinated by others of the mountain guerillas who favoured the Spanish cause.

The tide turned against the Spanish during the period of 1659-1660 when de Bolas and his men led a force of British soldiers to the Spanish encampment in Ocho Rios, where they killed half the Spanish forces. This was the beginning of the end for the Spanish who eventually fled the island for Cuba in April 1660. Three years later in 1663, the English Governor signed the first maroon treaty, granting de Bolas and his people land on the same terms as British settlers, to be enjoyed with the same liberties and privileges of the English, with some conditions, one of which was that their children must be raised in the English tongue. Juan de Bolas was named Colonel of the Black Militia, and he and others under his leadership appointed Magistrates over the negroes. This treaty, though the first of its kind, was later superseded by the Treaty of 1739, signed after the first Maroon wars ended. The Treaty of 1739 is known in the history books as the first Treaty between the British and the Maroons, overshadowing the pivotal accomplishments of Juan de Bolas and his maroon warriors without whom Jamaica's history may well have been much different.

Not all Maroons however, agreed with the alliance forged between de Bolas and the British. Juan de Bolas was eventually killed in an ambush, probably by Vermahalies under Juan de Serras's leadership. In 1670 after the murder of five hunters and six settlers in Clarendon, bounties were placed on the heads of the leadership of the Vermahalies and the government decreed that settlers traveling more than two miles should be armed, and anyone caught trading with the Vermahalies would be punished as an accomplice.

The next 60 years saw escalating tension with the British who could not dislodge the Maroons from their mountain fortresses. It was around 1720 that things really began to heat up. Cudjoe was rising in power among the Maroons in the west, while Quao and Nanny took a separatist approach holding together parts of the Windward Maroons, but never joining forces under a single leader like their counterparts in the west.

By 1720, the Maroons went on the offensive raiding British plantations along the base of mountains, eventually erupting into a state of open warfare between the British and the Maroons from 1729 to 1739.

Despite a declining population, the Maroons, occasionally augmented by a number of British owned slaves joining their ranks, dispersed across the island posing a serious challenge to the British for approximately 80 years.

Nothing paints a better picture than the words of someone who lived it; Philip Thicknesse, a British Lieutenant, who was given command of a party of soldiers that fell into an ambush by Maroons. For the remainder of this page, excerpts from the book Memoires and Anecdotes of Philip Thicknesse, will be used to describe in his own words, what was happening at the time.

Excerpt...

"... In Governor Trelawney's time, there were two formidable bodies of wild Negroes in the woods, who had no connection with each other, the west gang, under the command of Captain Cudjoe; the east under Captain Quoha. (p.92)

The Maroons in the west are considered the Leeward group occupying locations such as Trelawny Town in St. James and Accompong in St. Elizabeth. Those with settlements in the east are considered the Windward group, occupying such places as Moore Town and Charles Town in Portland, Nanny Town in St. Thomas and Scotts Hall in St. Mary.

After the defeat of the Spanish by the British, the Maroons who had continued to help the Spanish, after de Bolas opted to side with the British, continued their attacks against the British. Employing guerilla-like strategies, they relied on surprise and speed as they launched attacks with speedy retreats, quickly melting into the hilly and mountainous surroundings of the interior. Their intimate knowledge of the terrain made pursuit by the British very difficult. These tactics would have been perfected over generations by the time of the full scale war in the 1730s.

Excerpt...

"The mountains of the Island are exceedingly steep and high, much broken, split and divided by earthquakes, and many parts are inaccessible, but by men, who always go barefooted, and who can hold by withes, with their toes, almost as firmly, as we can with our fingers". (p.91)

Excerpt...

"... it may be necessary to give some account of the state of that island, between the years 1730, and that of 1739, when under the government of Mr Trelawney; who made permanent peace with those black people. Such who are acquainted with that island will be surprised when they are told, that all the regular troops in Europe, could not have conquered the wild Negroes, by force of arms; and if Mr. Trelawney had not wisely given them, what they contended for, LIBERTY, they would in all probability have been, at this day masters of the whole country". (p.91)

The Maroons were clearly a formidable force sufficiently adept at warfare, to prompt a British officer in concluding that the island would have been lost had Governor Trelawney not brokered a deal with them. A state of open warfare continued for two decades until the Maroons were offered a peace treaty by the English that was signed by Cudjoe, the leader of the Leeward Maroons on March 1st, 1739. This agreement however, did not apply to the Windward Maroons who were not involved and were unaware of the signed agreement.

Excerpt...

"... A straggling prisoner of Quoha's gang, being taken, he was sent to inform his brethren, with the conditions Mr. Trelawney held out to them, and which was accepted by Cudjoe long before Capt. Quoha, had heard any thing of it. (p.92)

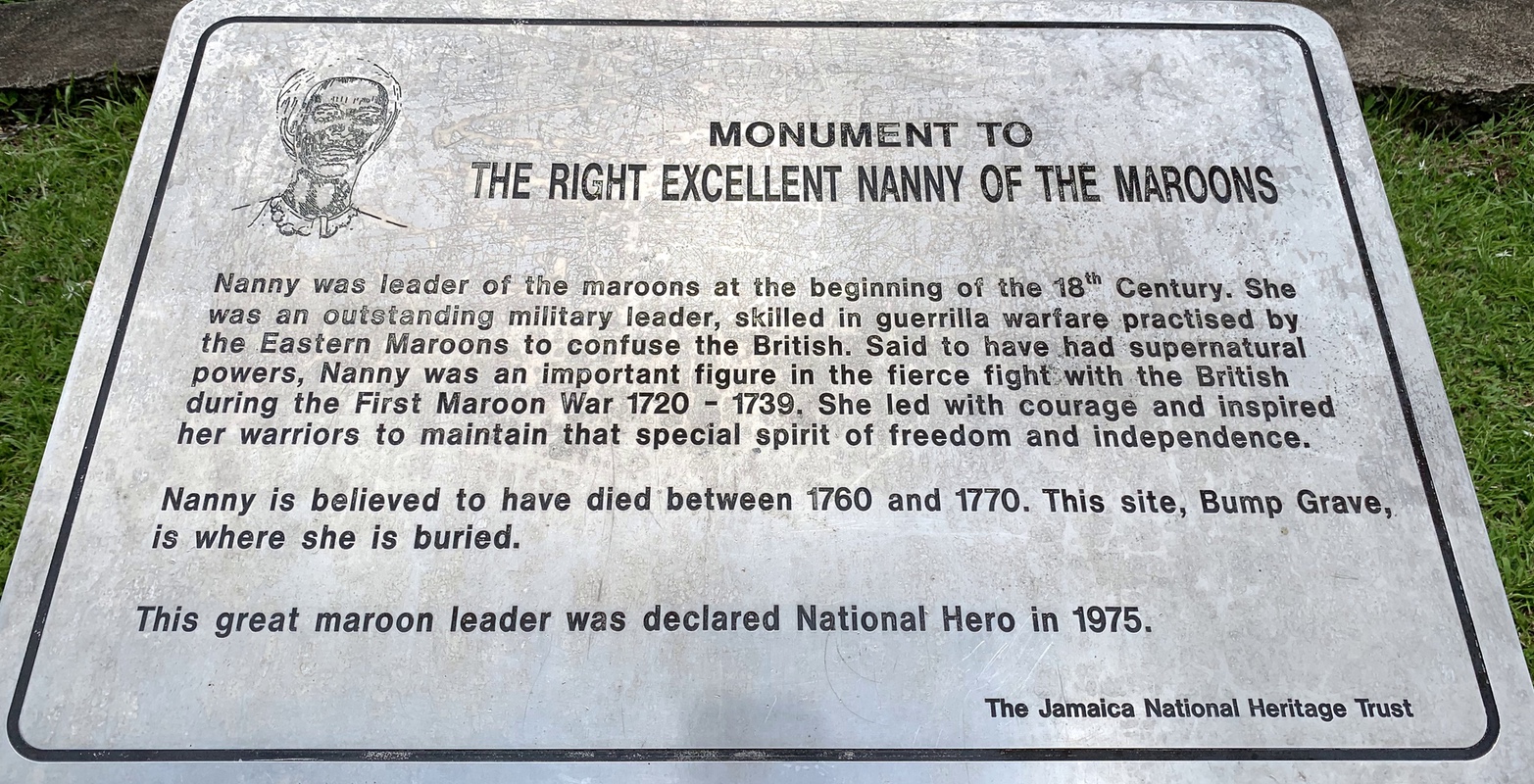

The Windward Maroons continued their offensive until they too, were also offered a treaty by the English. This treaty, which was signed by Quao, a leader of the Windward Maroons on 23rd December 1739, created a divide between the two factions of the Windward Maroons; those led by Quao and another led by Nanny, perhaps the most celebrated leader of the Moore Town Maroons. Nanny eventually agreed to peace when she signed an agreement the following year in 1740, ending the hostilities in return for freedom, autonomy and a land grant of of 500 acres. Today, the village built on the land grant is called Moore Town (also known as New Nanny Town), located in the mountains above Port Antonio.

Nanny was declared a National Hero in 1976, she is the only Maroon, and the only female, to have achieved such recognition. Her monument is located in Moore Town, Portland, Jamaica.

Nanny is reputed to have been a fierce fighter and strong leader during the First Maroon War from 1720 to 1739. A small, slim woman with piercing eyes, her influence over the Maroons stemmed from internal strength and a connection to the supernatural. Legends portray her as possessing the supernatural powers of obeah. She was a chieftainess whose battle plans confounded the British, uniting her followers through their shared history by passing down legends and encouraging them to embrace the customs, music and songs that had come with the people from Africa.

Driven by a strong sense of right and a spirit of freedom, she disagreed with Quao's decision to sign the Treaty on behalf of the Windward Maroons. She saw the principles of the negotiated peace with the British as another form of subjugation. Nanny's history is shrouded in mystery, her existence and conquests have been questioned by some because of limited documentary evidence but the lack of documentation is not surprising, considering the Maroon culture and history was predominantly passed down verbally, and oral tradition is more difficult to fact check compared to one that is documented. There are some sources that suggest that the below account from Thicknesse's memoires speak to her existence. The reference to the "Old Hagg" in the following passage is believed by some to be a reference to Nanny.

Excerpt...

Trelawney, with offers of submission upon the same terms, the laird had allured him, Cudjoe had accepted ; but said Quoha, when I consulted our Obea woman, she opposed the measure, and said, him bring becara for take the town, so cut him head off. But God knows what the poor laird suffered, previous to that kind operation. The old Hagg, who passed sentence of death upon this unfortunate man, had a girdle round her waste, with (I speak within compass) nine or ten different knives hanging in sheaths to it, many of which I have no doubt, had been plunged in human flesh and blood...

The Treaties that were signed 1739 by the Leeward and Windward Maroons ended the first Maroon-British war but slavery lasted for another century beyond that. As part of the agreement, the Maroons were obligated to return runaway slaves to the British and fight on the side of the British during any insurrection. A mission which they executed willingly, and often times with cold brutality, over the next 100 years. Refusing to cooperate meant risking everything they had achieved over 80 years of war.