No study of the Jamaica Great Houses would be complete without exploring the injustices visited on an entire people through their enslavement to build the plantations that produced the wealth, which enabled the building of these magnificent Houses.

It is because of the injustices meted out on these people why many of the Great Houses no longer exist. Many were put to the torch when the slaves rebelled against their masters and the system of slavery.

The slave trade between Africa and the West Indies was made illegal in 1807 and the traffic in slaves between the islands became illegal in 1811. However, it took another 26 years to effect the emancipation of the enslaved, when in 1833 Parliament passed the Slavery Abolition Act that finally abolished slavery in Jamaica and the other West Indian colonies on August 1, 1834.

There were many factors that influenced the legislation of 1833. There were doubts about the economic feasibility and the sustainability of slavery given the sustained resistance of the enslaved people that culminated in the major rebellion in Jamaica of Christmas 1831.

There was growing popular support for abolition but the negotiations toward that end were protracted, in part, because of the vested interest of those in the House of Commons and the House of Lords. In the end, the final terms resulted in the grant of £20 million in compensation payable by the British taxpayers, 40% of Britain's budget, to slave owners (equivalent to £2.6bn today).

Nothing went to the freed slaves to redress the injustices. The money went exclusively to the owners of slaves as compensation for the loss of "their property", the slaves. The Emancipation act also introduced a system of apprenticeship that tied the newly freed people into working for low wages under their old masters for a fixed term. The intent was to "help and train" the freed slaves to be free men and women. The quotation marks are inserted because the program was not to the exclusive benefit of the slaves. The owners also saw a benefit from the transition period in addition to being compensated.

The Emancipation Act of 1st August 1834 declared all children born into slavery under the age of six, and any born after that date, free. All other enslaved persons became apprenticed to their former masters up to 1st August 1838 -- praedials (field workers) for six years and non-praedials for four years -- after which, they were to be made free. Apprentices were obliged to work on the estates for 40.5 hours per week in exchange for food, clothing, and shelter, but not wages.

The wealth created in Jamaica by the labor of black slaves has been estimated at £18 million (£2.3bn today), more than half of the estimated total of £30 million for the entire British West Indies.

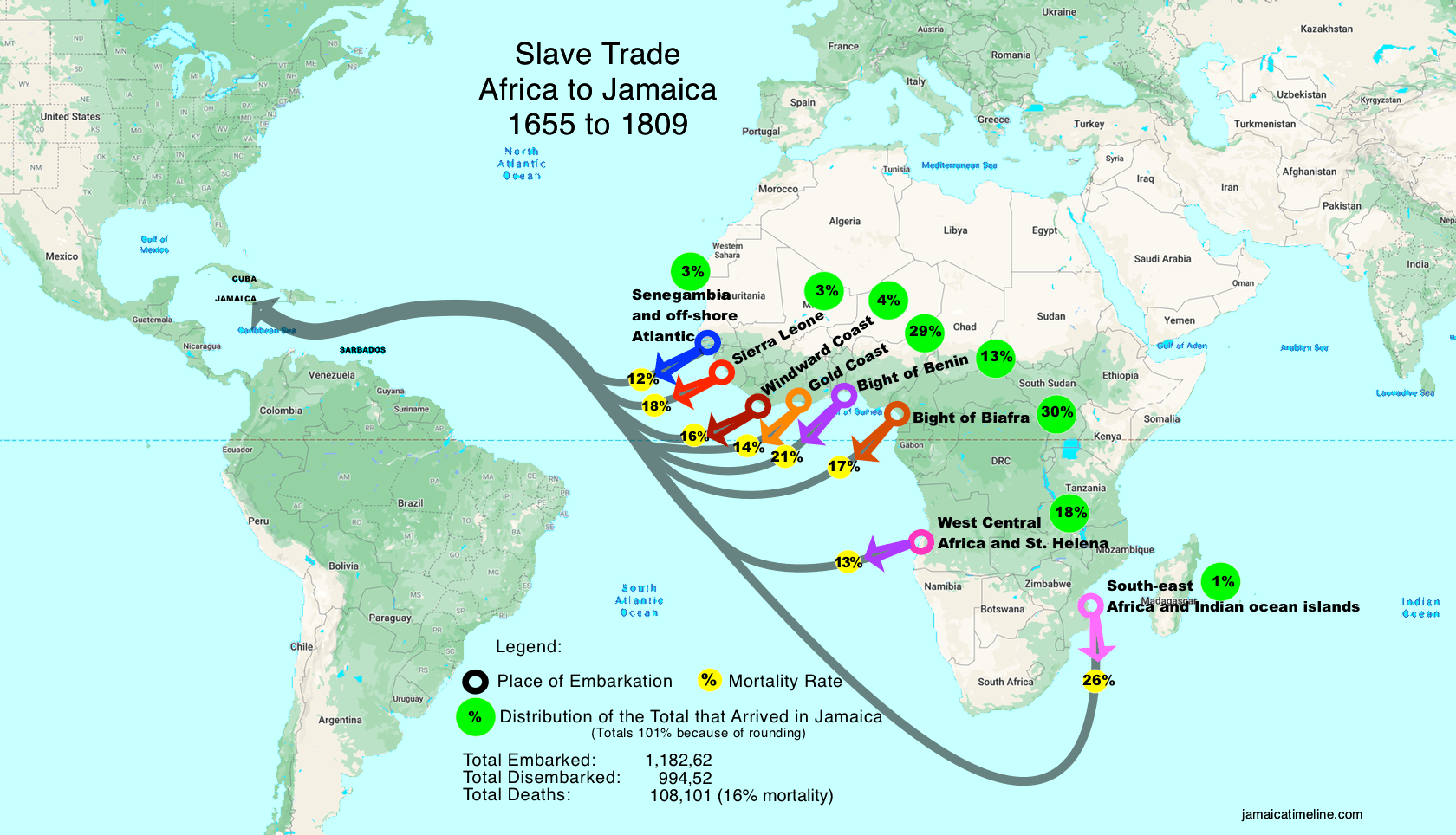

The transatlantic slave trade was a triangular route from Europe to Africa, Africa to the Americas and back to Europe. Merchants exported goods to Africa in return for enslaved Africans, gold, ivory and spices. The ships then travelled across the Atlantic to the American colonies where the Africans were sold as slaves to work on plantations and as domestics, for sugar, tobacco, cotton and other produce. The goods were then transported to Europe. There was also two-way trade between Europe and Africa, Europe and the Americas and between Africa and the Americas.

It is estimated that over 1 million slaves were transported directly from Africa to Jamaica during the period of slavery and of these, 200,000 were re-exported to other places in the Americas.

The demand for slaves required about 10,000 to be imported annually. Thus slaves born in Africa far outnumbered those who were born in Jamaica; on average they constituted more than 80 percent of the slave population until Britain abolished the slave trade in 1807.

There were many more slaves and far larger sugar plantations in Jamaica than there were in Barbados, which was the next largest producer of sugar in the Caribbean. Large estates in Jamaica had on average 400-500 slaves, with the largest ones having more than 1,000. Barbados being a much smaller island with much of the island already cultivated, saw a drop in slave population as smaller and less successful plantations folded. By contrast Jamaica's was growing.

New frontiers in Jamaica were opening up for sugar production, resulting in Jamaica becoming the leading point of disembarkation in the British Caribbean for slave ships. About 600,000 slaves disembarked in Jamaica between 1750 and 1808, more than four times the number disembarking in Barbados and more than any other island, British or otherwise.

| Years | Embarked | Disembarked |

|---|---|---|

| 1655 - 1675 | 22,203 | 16,999 |

| 1676 - 1700 | 94,436 | 71,785 |

| 1701 - 1725 | 161,644 | 134,481 |

| 1726 - 1750 | 225,537 | 185,760 |

| 1751 - 1775 | 272,038 | 219,137 |

| 1776 - 1800 | 330,816 | 298,752 |

| 1801 - 1809 | 75,952 | 67,611 |

| Totals | 1,182,626 | 994,525 |

The table below shows the same data broken down by the regions in Africa where the slaves embarked for the journey to Jamaica. An additional row has been added to show the mortality rate by region of embarkation.

| Years | Senegambia and off-shore Atlantic | Sierra Leone | Windward Coast | Gold Coast | Bight of Benin | Bight of Biafra | West Central Africa and St. Helena | South-east Africa and Indian ocean islands | Totals |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1651 - 1675 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 913 | 2,824 | 9,489 | 726 | 8,250 | 22,202 |

| 1676 - 1700 | 7,850 | 965 | 0 | 9,592 | 30,109 | 21,802 | 24,055 | 63 | 94,436 |

| 1701 - 1725 | 7,705 | 1,690 | 681 | 71,310 | 54,178 | 2,819 | 20,993 | 2,269 | 161,645 |

| 1726 - 1750 | 6,415 | 5,044 | 3,930 | 71,340 | 17,079 | 63,407 | 58,322 | 0 | 225,537 |

| 1751 - 1775 | 5,169 | 14,493 | 29,257 | 82,986 | 29,979 | 85,551 | 24,604 | 0 | 272,039 |

| 1776 - 1800 | 4,007 | 15,211 | 12,404 | 85,510 | 22,385 | 134,413 | 56,886 | 0 | 330,816 |

| 1801 - 1809 | 0 | 1,636 | 2,617 | 15,476 | 3,651 | 36,799 | 15,772 | 0 | 75,951 |

| Embarked | 31,146 | 39,039 | 48,889 | 337,127 | 160,205 | 354,280 | 201,358 | 10,582 | 1,182,626 |

| Deaths | 12% | 18% | 16% | 14% | 21% | 17% | 13% | 26% | 16% |

| Arrived | 27,325 | 32,177 | 41,055 | 289,009 | 126,296 | 294,812 | 176,008 | 7,847 | 16% |

| Origin of Arrived | 3% | 3% | 4% | 29% | 13% | 30% | 18% | 1% | 100% |

The ratio of blacks to white was an ongoing concern in Jamaica throughout the seventeenth to early nineteenth centuries, owing to the number of absentee owners and a lack of white laborers. Only a third of the Jamaican planters were resident on the island in contrast to Barbados, where two-thirds of its planters resided locally. Jamaica's imbalance of whites to blacks led to the creation of deficiency laws that were designed to maintain sufficient number of whites on each plantation relative to the number of blacks. The law established a ratio of white to black in an attempt to increase the white population through legal means. Any breach of the ratio resulted in a financial penalty.

At the heart of the concern about the ratio of slaves to whites was security and the fear of uprisings. A 1703 statute stipulated a ratio of one white person for each ten slaves, up to the first twenty slaves, and one for each twenty slaves thereafter but the masters found it easier to pay the fines rather than maintain compliance, so these laws in effect, amounted to a taxation. The problem persisted throughout the century and by 1763, the ratio was raised to 1 white for every 30 slaves, and/or 1 white for 150 head of cattle or 1 tavern or retail shop. These numbers were never achieved, so much so, in the annual meeting of the assembly, the taxes anticipated from the deficiency laws figured prominently in projected revenue estimates. In 1780, the parish of Westmoreland collected £1,722.05 as a deficiency tax from plantations with insufficient whites; 237 whites were supervising 7,839 slaves on 49 estates, a ratio of 1 white to 33 slaves. A shortfall of 24 whites.

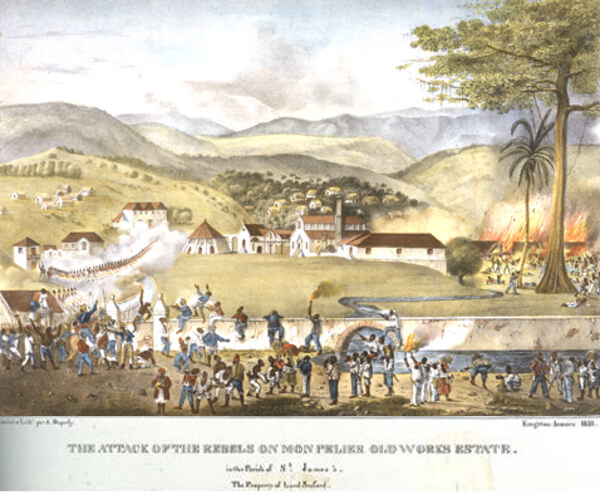

The slave uprising in 1831 is sometimes called The Baptist War or the Christmas Rebellion. Many of the rebels were Baptists by faith and it happened over an 8 day period (some sources report up to 11 days) including Christmas day of 1831. As many as sixty thousand of Jamaica’s three hundred thousand slaves in 1831–1832 rose up across the island against their masters.

On Tuesday, 27th of December, 1831, a fire at Kensington estate in St. James, one of the most important sugar growing parishes in Jamaica, marked the outbreak of a slave rebellion which swept the western parishes of the island. The Kensington Estate Great House was the first house to be set alight as a signal that the rebellion had begun.

Over the following days, many of the remaining Great Houses, were destroyed, with a only a very few that went untouched.

There are only a few remaining today that are in good repair. Some are private homes, some are located on private resorts, some privately owned but are open to the public for tours, while others are in the hands of the National Heritage Trust.

"I would rather die upon yonder gallows than live in slavery"

In 1831, Jamaica experienced what is considered one of the largest, longest and most influential slave rebellions of the three emancipation era revolts in the British Caribbean.

In Jamaica at the time, slaves far outnumbered their white counterparts by twelve to one (12-1). Samuel Sharpe, a self educated slave, was born in Jamaica in 1801. He joined the church and became a Baptist deacon. He used that platform to inspire his congregation as he raised his concerns on the injustices of slavery. He instigated a peaceful rebellion; a general strike against slavery. The plan was to have slaves refuse to work after the 1831 Christmas holiday until the plantation owners listened to their grievances. The strike was timed for the most leverage; at a time when the sugar cane needed to be harvested and would be ruined if not cut.

He encouraged peaceful resistance, but did not completely denounce physical violence if it was needed. Sharpe had also made military preparations with a rebel military group known as the Black Regiment, about 150 strong with fifty guns among them, led by a slave known as Colonel Johnson of Retrieve Estate.

As the idea of the strike permeated across the island, it came to the ears of some slave owners. Aware of the plan, troops were sent to St. James and warships were anchored in Montego Bay and Black River with their guns trained on the towns.

On December 28 1831, the Kensington Estate Great House was set alight as a signal that the rebellion had begun. It was soon apparent that hope for peaceful resistance had failed as other fires were struck. Colonel Johnson's Black Regiment clashed with a local militia led by Colonel Grignon at old Montpelier on December 28. The militia beat a strategic retreat to Montego Bay while the Black Regiment further invaded estates in the hills, inviting more slaves to join them, burning houses, fields and other properties on the border of St. James, setting off a trail of fires through the Great River Valley in Westmoreland and St. Elizabeth.

The rebellion lasted for 8 days and resulted in the death of around 186 slaves and 14 white overseers or planters. It is said that the militia took control of the rebellion by the end of the first week in January, but historians have noted that suppression took fully two months because of the slave's guerrilla tactics, and the terrain.

The militia solicited the help of the Maroons, and with their assistance and cooperation the militia acted with excessive savagery against the slaves as they rounded them up in the mountains. The Maroons from Moore Town and Charles Town were shipped into Falmouth to further assist. Women and children were shot on sight and slave homes and provision grounds were systematically burned. There were numerous judicial murders by summary court martial, a simplified procedure for the resolution of charges.

It is reported that 14 free colored died in the rebellion, 200 slaves died in fighting, 312 executed and 300 flogged. In all, 626 were tried and 312 executed. Executions mainly took place in the form of hanging as 72% were hanged while 28% were shot. In St. James, slaves were gibbeted and erected in the public square in the center of the town. In Lucea, the condemned were put in carts, with their arms pinioned, ropes around their neck and white caps on their heads, they eventually met their death. The Baptists were blamed more than any other church groups, as it gave authority to black deacons.

Sam Sharpe was named as the key figure behind the resistance. He was captured and hung on May 23, 1832 in Montego Bay, on a square now called Sam Sharpe Square. His owners were paid the sum of just £16.00 for their "loss of property".

As many as 60,000 of Jamaica’s 300,000 slaves in 1831–1832 rose up across the island against their masters. It was considered the largest slave rebellion in the British Caribbean, and was a major catalyst to the eventual Emancipation Act that was passed in the English parliament 2 years later.

The 1831 slave rebellion hastened the passage of Emancipation and Sam Sharpe has been declared a National Hero.

| Parish | Total Tried | Total Executed |

|---|---|---|

| Hanover Courts Martial | 58 | 27 |

| Hanover Civil Courts | 82 | 60 |

| Trelawny Courts Martial | 70 | 24 |

| St. James Courts Martial | 99 | 81 |

| St. James Civil Courts | 81 | 39 |

| Westmoreland Courts Martial | 26 | 12 |

| Westmoreland Civil Court | 52 | 20 |

| St. Elizabeth Courts Martial | 73 | 14 |

| Portland Courts Martial | 23 | 7 |

| Portland Civil Courts | 5 | 5 |

| St. Thomas in the Vale Courts Martial | 9 | - |

| Manchester Courts Martial | 15 | 13 |

| Manchester Civil Courts | 16 | 7 |

| St. Thomas in the East Courts Martial | 12 | 1 |

| St. Thomas in the East Civil Courts | 5 | 2 |

| Total | 626 | 312 |

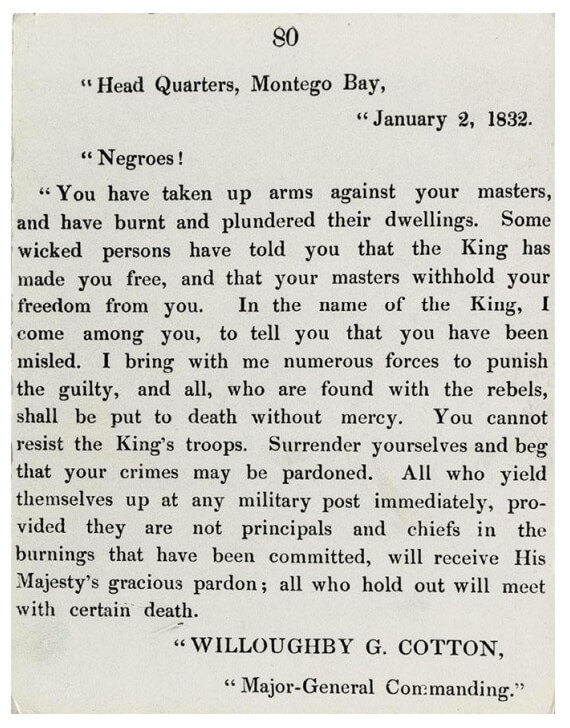

Newspaper clippings of articles published in 1832 in the United Kingdom about the rebellion. A transcription is provided along with a image of the actual newspaper articles... [ more ]