The Cherry Garden Great House, located in the parish of St Andrew, has links to two prominent figures in Jamaica's and North America's, history; it was home to George William Gordon, a National Hero of Jamaica, and years before that, was associated with Jonathan Dickinson, an influencial business man who eventually became a politician and mayor of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Jonathan Dickinson was the brother of Mary Gomersall, wife of Ezekiel Gomersall, the first owner of the house.

The Cherry Garden Great House sits on about 2 acres of what was the Gomersall sugar plantation in the 17th century. The owner of the plantation, Ezekiel Gomersall (1663-1734), was one of the largest slave owners in Jamaica and the single largest purchaser of slaves in the parish of St. Andrew. He was also one of the counsellors, or commissioners that oversaw one of the more famous trials in Jamaica's history; the trial of Anne Bonny and Mary Read, the infamous female pirates associated with Captain Rackham, aka Calico Jack.

Ezekiel expanded the plantation over a period of 20 years from 1694 to 1714 to about 300 acres by purchasing and annexing several parcels. Today, the Cherry Garden Great House sits on a fraction of the original land, surrounded by expensive residential homes in the Cherry Garden residential area.

Gomersall's first wife, Mary, was from a notable family of landowners. Her father, Captain Francis Dickinson had been granted 6,000 acres, which included Appleton Estates (the producer of today's Appleton Rum), by King Charles II as a reward for his service in the capture of Jamaica from the Spaniards in 1655. After Gomersall's passing in 1734, the Cherry Garden estate was passed on to his second wife, Elizabeth Garthwaite (remarried after his death) and Ezekiel Dickinson, the nephew of his first wife.

In the years leading up to Emancipation the property was administered by Joseph Gordon, an attorney from Scotland who oversaw several properties for a number of absentee landowners. He was the father one of Jamaica's National Hero, George William Gordon and over time, became a very significant landowner himself.

In 1845, George William Gordon bought and expanded the Cherry Garden property by purchasing adjoining lots. George William lived at Cherry Garden until he was arrested and later hanged for his alleged role in the Morant Bay Rebellion of 1865.

The Cherry Garden great house and its grounds is today, a shadow of its former self. The house has several features associated with the Great Houses of the time. The design made provisions for ventilation and illumination, through the use jalousie windows along the main wall, punctuated by intermediary casements. These jalousie windows extended from the chair rail level up to the underside of the wooden beams or joist supporting the floor level above.

A verandah to the back extends the interior living space to the outdoors on both the ground and upper floors, another feature typical of the period . The upper floor is accessible via an interior and an exterior staircase. A practical feature that allowed the interior to be closed off during hot days, without impeding access to both floors from the inside or outside living spaces.

The interior staircase, made of hardwood, is located to the left of the front entrance. It ascends to the upper floor that is also built to facilitate the cooling winds and sunlight without the full effect of the heat of the sun through the use of jalousie windows along the exetrior wall.

The exterior staircase is located to the back of the house, providing ingress and egress to the upstairs verandah.

Also typical of the period was the location of the kitchen. Built as a separate structure, the kitchen is built to the back of the main building to mitigate the risk of fire in the main dwelling, as well as for the practical purpose of not introducing additional heat to the main dwelling. The original kitchen is no longer there, but the walkway between it and the main house still exists, albeit adorned with more modern material from that which would have been used back then. This walkway would have seen a lot of foot traffic on a daily basis in its heyday.

The Cherry Garden Great House sits on about 2 acres, a fraction of what was a very large sugar plantation in the 17th century. Over the course of 20 years, Ezekiel Gomerall expanded his plantation from 1694 to 1714 to about 300 acres by purchasing and annexing several parcels. Today, the property is a majestic older home in a residential community that spreads on the foothills of some of Jamaica's highest and most beautiful mountain ranges.

Nothing captures the spirit and sense of the grounds, the gardens and the views from Cherry Garden great house in the nineteenth century, than the memories captured by the british historian, writer and traveler, James Anthony Froude, when he visited the Cherry Garden estate in 1888...

Extract from "The English in the West Indies: Or, The Bow of Ulysses,

by James Anthony Froude"

The house was large, with fine airy rooms, a draught so constantly blowing through it that the candles had to be covered with bell glasses; but the draughts in these countries are the very breath of life.

It had been too dark when I arrived to see anything of the surroundings, and the next morning I strolled out to see what the place was like. It lies just at the foot of the Blue Mountains, where the gradual slope from the sea begins to become steep. The plain of Kingston lay stretched before me, with its woods and cornfields and villas, the long straggling town, the ships at anchor in the harbour, the steamers passing in and out with their long trails of smoke, the sand-spit like a thin grey line lying upon the water, as the natural breakwater by which the harbour is formed, and beyond it the broad blue expanse of the Caribbean Sea.

The foreground was like an English park, studded over with handsome forest trees and broken by the rains into picturesque ravines. Some acres were planted with oranges of the choicer sorts, as an experiment to show what Jamaica could do, but they were as yet young and had not come into bearing.

Round the house were gardens where the treasures of our hot-houses were carelessly and lavishly scattered. Stephanotis trailed along the railing or climbed over the trellis. Oleanders white and pink waved over marble basins, and were sprinkled by the spray from spouting fountains. Crotons stood about in tubs, not small plants as we know them, but large shrubs; great purple or parti-coloured bushes. They have a fancy for crotons in the West Indies; I suppose as a change from the monotony of green. I cannot share it. A red leaf, except in autumn before it falls, is a kind of monster, and I am glad that Nature has made so few of them. In the shade of the trees behind the house was a collection of orchids, the most perfect, I believe, in the island.

And here Gordon had lived. Here he had been arrested and carried away to his death; his crime being that he had dreamt of regenerating the negro race by baptising them in the Jordan of English Radicalism. He would have brought about nothing but confusion, and have precipitated Jamaica prematurely into the black anarchy into which perhaps it is still destined to fall. But to hang him was an extreme measure, and, in the present state of public opinion, a dangerous one.

One does not associate the sons of darkness with keen perceptions of the beautiful. Yet no mortal ever selected a lovelier spot for a residence than did Gordon in choosing Cherry Garden. How often had his round dark eyes wandered over the scenes at which I was gazing, watched the early rays of the sun slanting upwards to the high peaks of the Blue Mountains, or the last as he sank in gold and crimson behind the hills at Mandeville; watched the great steamers entering or leaving Port Royal, and at night the gleam of the lighthouse from among the palm trees on the spit.

In 1820, a black female slave on the Cherry Garden Estate gave birth to the son of her white Scottish slave owner, Joseph Gordon. The boy was named George William Gordon.

Joseph Gordon was a powerful planter-attorney from Scotland, one of only four attorneys who had control over more than 20 properties on the island in 1832. Over time, he too became a prominent landowner and a member of Jamaica's legislative Assembly and custos of St Andrew.

The boy, George William, was predominantly self-taught, teaching himself to read and write and at the age of 10 was sent to live with James Daly, his godfather who was also an attorney for two estates, a businessman and owner of slaves in Black River, St Elizabeth. While there, George William learned the skill of bookkeeping and proved to be an asset his god father's business.

George William returned to Kingston in 1836 at the age of 16 where he started a business, and over time flourished as a successful business man owning large land holdings in the parish of St. Thomas. His father who had married a white woman and had three girl children, had fallen on hard times amd was on the verge of losing the Cherry Garden estate. He approached George William for help who provided assistance and monetary support, saving the Cherry Garden estate in the process. George also paid for the passage of his half sisters to England and France and for their education. Joseph Gordon also left Jamaica and George William assumed all his father's responsibilities and agreed to pay him £500 a year.

George William bought the Cherry Garden property in 1845, and expanded it by purchasing adjoining lots. He lived at Cherry Garden until he was arrested and later hanged for his alleged role in the Morant Bay Rebellion of 1865.

George William Gordon had become a wealthy business man, magistrate and politician. He was a leading critic of the colonial government and the policies of Jamaica's Governor Edward Eyre. His experience and memories as a mulatto slave growing up on the Cherry Garden estate, likely contributed to him entering politics and representing the interests of the poor and underpriviledged people who did not have voting rights. He subdivided his own lands and sold lots at low prices to the people for farming. He also helped create a organized marketing system for them to sell their produce at fair prices.

As a critic of the local and colonial government, Gordon urged the people to protest and resist the oppressive and unjust conditions under which they were forced to live. He was arrested and charged for complicity in what is now called the Morant Bay Rebellion in 1865. He was illegally tried by Court Martial and despite a lack of evidence, was convicted and sentenced to death. He was executed on October 23, 1865.

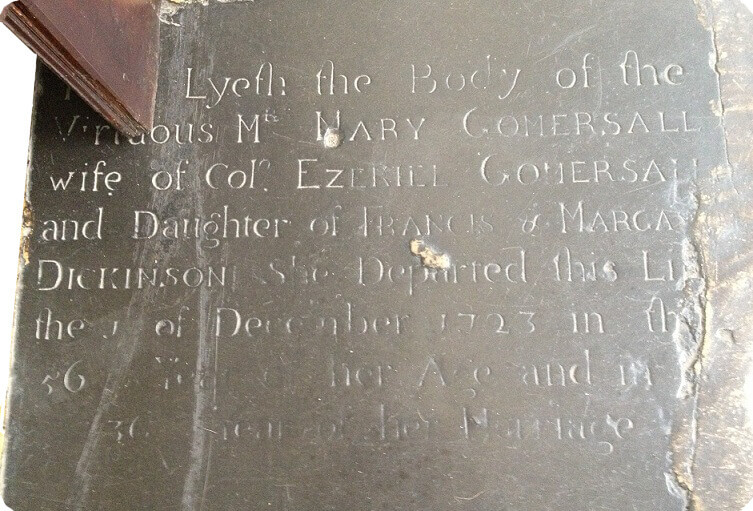

Here Lyeth the Body of the Virtuous Mrs. MARY GOMERSALL wife of Col. EZEKIEL GOMERSALL and Daughter of FRANCES & MARGARET DICKINSON. She Departed this Life the 1st of December 1723 in the 56th Year of her Age and in the 36th Year of her Marriage.

Here Lyeth the Body of the Virtuous Mrs. MARY GOMERSALL wife of Col. EZEKIEL GOMERSALL and Daughter of FRANCES & MARGARET DICKINSON. She Departed this Life the 1st of December 1723 in the 56th Year of her Age and in the 36th Year of her Marriage.

Ezekiel Gomersall, the first owner of the Cherry Garden great house, was born in 1663 and died in 1734 at the age of 70. He was married twice; first to Mary (nee Dickinson) for 36 years then to Elizabeth (nee Douce) after Mary died. On his death, he left the Cherry Garden estate to Elizabeth (who later married *Edward Garthwaite) and to Ezekiel Dickinson, the nephew of his first wife, Mary. Ezekiel Gomersall was buried at the Kingston Parish Church.

Ezekiel Gomersall was also one of the commissioners that oversaw one of the more famous trials in Jamaica's history; the trial of Anne Bonny and Mary Read, the infamous female pirates associated with Captain Rackham, aka Calico Jack, who 11 days earlier, had been hung outside of Port Royal. The women were to be tried under the harsher laws of the High Court of the Admiralty, in a military-like trial with no legal-representation, a process that was the norm for piracy and relied on the death penalty as the ultimate punishment.

On Monday, November 28, 1720, the women were marched in chains into a packed courtroom in the courthouse near the old spanish plaza in St Jago de la Vega (Spanish Town). The novelty of two female pirates and the news of their capture had caught the attention of a large crowd, gathered to witness their fate. The two women stood before Ezekiel Gomersall, Samuel Moore, James Archibald, John Sadler, Thomas Bernard, the then Governor Nicholas Lawes and William Nedham who served as the Chief Justice. The court unanimously agreed on the verdict of death without much contemplation.

Ezekiel Gomersall's first wife, Mary Dickinson was from a family of Quakers, a group with Christian roots that began in England in the 1650s. They owned several large properties; Appleton, Pepper, Barton Isles, Bona Vista and Watchell in the parish of St Elizabeth (the parishes were a lot different then). The landholdings originated from a grant of 6,000 acres to her father, Francis Dickinson, by the King of England. Francis was also the brother of Edmund Dickinson, personal physician to King Charles II.

Mary's brother, Caleb Dickinson, inherited his father's estates, and Caleb's son Ezekiel, inherited the Cherry Garden estate. The Dickinson family maintained their ownership in the Cherry Garden estate up until the time when ownership was transferred to Joseph Gordon, the father of George William Gordon and the attorney of Jeremiah and Ezekiel Harman, the great grand children of Caleb Dickinson.

Mary's other brother, Jonathan Dickson, went on to play an important role in Jamaica's and North America's history. Jonathan became a trans-Atlantic merchantman, a ship-owner and slave-trader, smuggler, survivor of a shipwreck and capture by an indian tribe and a Philadelphian mayor, just to name a few of his adventures, professional accomplishments, misfortunes and exploits.

In 1696, Jonathan Dickinson left Port Royal his home port, for Philadelphia with his family and 10 slaves on a ship called Reformation. The ship got separated from the main fleet and wrecked along the coast of Florida where they were captured by a hostile indian tribe called the Jobe. Fearing for their lives and facing hostility for days, they were eventually let go and travelled 230 miles to St Augustine... an ordeal that took 49 days. Jonathan eventually made it to Philadelphia where he later wrote an account of his harrowing experience in a book called "God's Protecting Providence". The book has been reprinted 25 times in English, German, and Dutch. There is a State Park in Florida named after him, commemorating his experience.

Jonathan's journal is an inspiration of survival and faith. His book describes his Florida experience and gives one of the first and most detailed accounts of early Florida (which was under Spanish rule). It discusses seventeenth-century plants, animals, and Spanish missions or "churches".

In Philadelphia, Jonathan's merchant business became very successful, becoming one of the richest men in Philadelphia, owning much real estate. He held a number of political positons in Pensylvania, including the Speaker of the Pennsylvania Assembly, several terms as an alderman for the city of Philadelphia during 1711-1720, justice of the Supreme Court from 1711-1712 and twice Mayor of Philadelphia from 1712-1713 and 1717-1719.

Jonathan made several trips between Philadelphia and Jamaica, sometimes remaining in Jamaica for years at a time to attend to his business interests. Several letter books of his, held at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania and the Library Company of Philadelphia, provide a glimpse into his life. By maintaining nearly 10,000 acres in Jamaica, and a vast amount of real estate in Pennsylvania as well as trading on four continents, Jonathan Dickinson created a historical treasure trove of useful information for historians.

Jonathan kept in close contact with his his brother-in-law, Ezekiel Gomersall, who was one of the largest slave owners in Jamaica and the largest purchaser of slaves in St Andrew. Many of their exchanged letters still exists today. This connection was an important part of Dickinson’s transatlantic trades. Jamaica was suffering from a shortage of laborers. Slaves were not getting to the island fast or cheaply enough. The letters between Jonathan and Ezekiel, covered a diversity of topics, from the slave trade, to the glut of sugar produced in Barbados and its impact on the price of sugar to questions on the feasibility and legality of conducting trade with the Spanish and the French.

Several of Jonathan's letters and writings paint a graphic picture of the inhumanity of the slave trade. In one of his letters to his brother-in-law, he mentions a slave who died shortly before arriving in Philadelphia for which he had to pay fifteen-shillings in burial costs. He went on to mention that "if slaves did not die shortly after arriving they were still oftentimes sickly". His commentary is an interesting though saddening (if not sickening) juxtaposition; his view of a person's ailment and mortality as a deficit to his economic circumstance, a stark contrast to the reality; the insensitivity of the slave trade to human suffering and fatality. A trader viewing them only as a commodity; an investment or a liability... health = wealth, sickness = liability, death = economic deficit. This is a not a judgement of the man, but a commentary to the mindset of the time.

Jonathan Dickinson died on June 16, 1722, in the city of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

(*) Notes: